This hike had lots of type two fun. There were times when I was tired and concerned, but there were also times when I took in the beauty and isolation and felt an enormous sense of accomplishment. The newness and times of concern were qualities that made this hike fun.

I wanted to have some fun in the backcountry. I was tired of working out logistics, doing tedious hikes, and being around hikers that do not respect nature or other hikers. Simple logistics, no lame treks, and isolation were the prescription. Sometimes logistics are a pain. If not in the right mindset, figuring out how to get to the trailhead and get home can be stressful.

On the other hand, simple hikes without physical and mental challenges are unfulfilling. Going over two high passes is physically challenging, and being on a new route, alone and with unknowns, will be mentally tough. The trip is short, so the grueling effort to improvise, adapt, and overcome has immediate satisfaction. Besides, I love isolation because I experience nature on my terms. By being a solo hiker, I see and experience more of nature without the tags and labels of people. However, I love sharing the experience with those with the same mindset and hiking abilities.

For this trip, the mental goals were as important as the physical and visual experiences. Fun was the name of the game. The fun constituted seeing the Colorado backcountry in an unspoiled wilderness area, solitude, physical exertion, and having a sense of accomplishment.

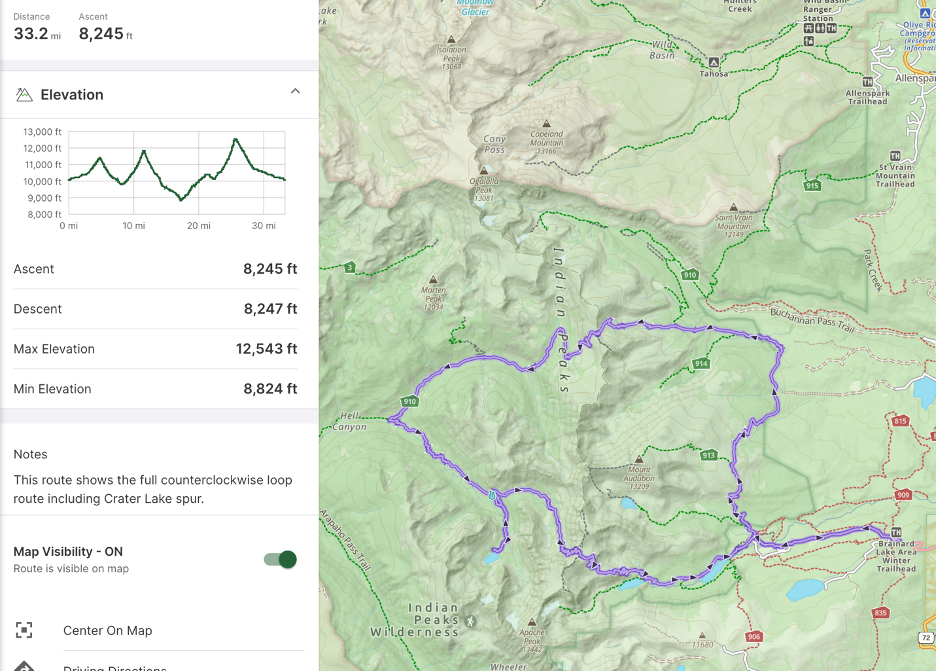

The logistics were easy because the trip was close to home, short, and in a loop. This hike is in the Indian Peaks Wilderness, which requires backcountry reservations to limit the number of people. I split the trek with one overnight stay after going over Buchanan Pass. The second day is the very challenging Pawnee Pass approaching it from the west. For both passes, I did the steeper ascent.

Pawnee Pass is a physical and mental challenge because the ascent is class 2 and steep. A recent rockslide that wiped out the trail at the most vertical section makes it even harder. During the hike, I became more concerned because most people thought I was crazy going over Pawnee Pass, but these people stayed west of Pawnee Pass. However, I met two trail runners descending the pass, and they said to be careful.

I could not get an overnight parking pass, so I parked at the Brainard Lake Winter Trailhead, which does not require a parking permit and allows overnight parking but adds 6 miles to the loop. I got to the parking area around 07:00 and started the 3-mile road walk to the trailhead, getting to the trailhead around 08:00. The trail was beautiful, and not a soul in sight. After a few miles, I came up to another solo hiker. She was also making the two-passed loop in three days instead of two. She was from Wisconsin, worked at a youth camp, and was on a cross-country trip to visit friends in Seattle.

I saw many colorful and noticeable mushrooms on the route, sometimes over 8 inches across. I wonder if the increase in moisture this year increases the number of mushrooms since I have never seen so many.

I took plenty of breaks and kept scanning the sky for storms. I was not worried about hiking 18 miles, even with over 4,000 feet of ascent, and I was going to go as far as possible with my permit to make the next day over Pawnee Pass easier. In the Indian Peaks Wilderness, the USFS grants backcountry permits to limit the number of people. I know the USFS does not have enough people to enforce permits, but I respect the concept and only take advantage of no enforcement for safety reasons. For example, I did not camp in my designated spot in the Saguaro National Park because of the weather and darkness.

Shortly after getting over the pass, light hail started. I got into the trees, and it increased and included rain. I did not hear any thunder or see lightning. The way down was muddy in spots but lush and beautiful. Waterfalls were frequent along the trail, with stream crossings happening every two miles. The rain soaked my shoes, but my feet were warm. I wore my rain jacket, and my shorts quickly dried in the sunshine.

At one stream crossing, I met another solo hiker who had come into the wilderness from the west. He was already camped and was fishing. He knew what he was doing and even brought two fishing poles, one for streams and one for lakes. He carried about 50 pounds of gear and only did 10 miles daily. He often would spend multiple days at a site.

I liked that he respected what I was doing with an 18-pound pack, and I respected what he was doing by living in the backcountry. We spoke about the conditions, and he was concerned that I was going over Pawnee Pass. His concern was the first I had heard of the recent rockslide.

I told him where I planned to spend the night, and he said he just had spent two nights there, and there were two good camping spots. We wished each other well, and I continued hiking.

A couple of miles later, I ran into four men hiking. They entered the wilderness from the west and were going to camp in a mile or so before doing Buchanan Pass the next day. They were all jovial and enjoying the hike, even in the rain.

A few miles later, I hit the intersection of the Buchanan Pass and the Cascade Creek trails, and shortly after that, I saw the campsites the solo hiker mentioned. I took my time choosing a tent location and setting it up since I had three hours before sunset.

The camps were near waterfalls. The rain stopped, but the ground was wet. A bull moose drank at the creek, but the trees impeded my view. I found an excellent place to do a two-tree bear hang and a location away from my tent to eat.

I cold-soaked mashed potatoes and tuna and enjoyed a nutrition bar for dessert. Water would not be a problem, and I could take one liter on the approach to Pawnee Pass the next day. After the pass, there would be lakes and streams to get water.

My feet got wet from the rain. I always bring a spare pair of socks, so one set can dry while the other is worn. Because of the dampness and camping near a stream, my shoes did not dry overnight. I had dry socks, which wick away moister, so my feet became comfortable as I hiked the next day.

I was tired but not sleepy, so I listened to “The Lincoln Highway” audiobook. I dozed off and had a fitful night’s sleep. I should have taken a sleep aid, but I was hard-headed. My hardheadedness is a common theme that I need to break. I got up before sunrise, packed in 40 minutes, and started hiking.

The Cascade Creek Trail gradually rose over the few miles, crossing the creek several times. I saw many moose. After I left camp, the bull snorted at me, so I would leave him alone. A couple of miles later, I found a herd of moose grazing. This trip was the first one where I saw more moose than deer and elk.

After crossing Cascade Creek for the third time, I stopped and heated some water for oatmeal and snacked on a bar. The morning warmed, and I did not need to keep hiking to stay warm. I hydrated and made some water for the push. A backpacking couple came down the trail. They had been at Crater Lake and were exiting the wilderness. Like most people, they entered Indian Peaks Wilderness from the west and did not have any information.

Crater Lake is beautiful and has a dramatic view of Lone Eagle Peak. I could not get a permit for one of the campsites around Crater Lake since they are in high demand. I probably could have camped here or near here, but my respect for the environment and LNT principles made me simplify my life and just camp where I did.

After Crater Lake, the steep climb started. I saw a trail runner coming down, and he confirmed the poor, dangerous trail and said to be careful. The terrain became rockier and had less tree cover. The marmots became plentiful and chirped as I made my way up.

I like to think that their chirps are encouraging me to keep going, but I know that they are communicating with others that a smelly human is in their territory. I began to wonder what they do in the winter. This area gets at least 10-15 feet of snow, so their food (plants, insects, bird eggs) does not exist. They have dens, so they must hibernate. I confirmed my guess and learned that they hibernate up to eight months a year, depending on the snowpack and weather. Marmots must be hearty. I’ve seen them in rock fields up the highest peaks in Colorado.

I passed Pawnee Lake. I might have taken a short side trip to the lake, but the terrain looked marshy, and I wanted to get over the pass before storms rolled in. Besides, the climb up to Pawnee Pass was going to be difficult.

I could not see the path to the pass and thought, “the trail would provide.” Besides, a trail runner had recently come over. I got into the rock field, and the track became steeper. A rockslide destroyed the trail, but cairns were visible in sections where the trail disappeared under the rock. I thought (and hoped) that this section was where the rockslide was. Nope!

I left the rockslide area and ran into another trail runner coming down. She confirmed that the dangerous rockslide was still ahead and that I should be careful. I told her there was another one a couple hundred feet below, but cairns marked the path. She laughed and heroically said she was heading down, so she would not fall far if she fell lower. She had some gallows humor after getting through the rockslide. I laughed and thought – oh shit!

There was no going back. Besides the impracticality of turning around, I would not give up. I can’t give up! After another fifty feet of ascent, the trail disappeared, and I came onto the rockslide. There were no cairns; I could not see the route ahead. I started traversing the rocks and scrambling on all fours. I lost a water bottle and felt awful because I did not descend 50 feet over the unstable rockslide to retrieve it. I left a trace, damn it! I was scared but shoved that emotion to hide deep in my consciousness and kept going, making sure each hand and foothold were secure and planning my next moves. I slid once, and I caught myself. I kept three points of contact while scrambling. I checked my pants, and my tight sphincter did its job. I made it through.

I came across a quote that sums up why I challenge myself.

“Everything you’ve ever wanted is on the other side of fear.”

George Addair

I am not a mountaineer, but I estimated that the rockslide area was a Class 2 hike on the Yosemite Decimal System. Handholds were necessary, falls could be fatal, and the short climb was very exposed. The slope was between 40-50 degrees, but I made my way by making switchbacks.

I traversed, climbed out of the rockslide, and found the trail. There were no signs of the path. I think I saw a trekking pole hole at one point. The route ascended another ten feet and came out on a grassy area up to the official signage.

Getting to the top of any pass or summit is a great accomplishment, but the top of the Pawnee Pass was unique because of the perceived danger. In hindsight, I made more of the ascent than it warranted. Still, when I got to the top, I met a woman and her dog, Gypsy, who got to the top of Pawnee Pass from the east side but did some bushwhacking to get from their trail to the pass. She said the website said the route was closed and had been for over a week, and the website had a big red banner at the top saying so.

Well, shame on me. I must have ignored the big red banner. Also, I find it weird that I remember a dog’s name but cannot remember a person’s name. So be it. The woman was very nice. She has backpacked all the named trails in the Indian Peaks Wilderness and works with troubled youths at a wilderness camp. She was the second person I met who worked at a youth camp. Gypsy’s owner and Gypsy live in Colorado Springs.

On the way down, we passed a youth group and a guide/teacher from a local high school climbing to the pass. Schools recently started, and many schools have outdoor bonding exercises. Gypsy’s owner talked about how much youth benefit from such activities, and I could not agree more.

We hiked down past Isabelle’s Glacier and Lake. I stopped for water, and they hiked on because of the impending thunderstorm. They did not have raingear, and I did. Besides, by my dead reckoning, I would make my car by 15:00 and be home by 16:00, so I was not going to push it. The climb took it out of me.

The number of people I saw grew as I got closer to the trailhead. Unfortunately, most people headed up the trail and ignored the impending bad weather. I worried about the youth group, but they were prepared and likely heading down. Looking at the faces of the group, they were mostly smiling, which is terrific since other groups usually look at me with deadly piercing eyes like I am the one to blame for their physical discomfort.

Thunder, lightning, hail, and rain turned the trail into a river. I had put on my rain jacket but not my rain pants. The temperature was not cold enough. The people who passed me on their way up were running down to get out of the rain. A trail runner and her dog caught me at the Long Lake TH. The rain drenched her and her dog. We greeted each other, and she headed her way, and I mine.

She caught up to me a few minutes later, and we laughed. The road loops and her brochure-type map confused her. I told her I was heading to the Brainard Lake Winter TH, outside the recreation area. I asked where she was heading. She said the day parking area, and I showed her on GAIA where I was going and where she likely needed to go. She thought about it and headed off.

She caught me again a few minutes later as I was hiking by the day parking area. She said that her car was likely nearby and offered me a ride to my vehicle. She was so lovely. I still had a couple of miles of road walking. She dropped me off at my car, and I was home by 15:00.

Lessons Learned

Overcoming Mental and Physical Stress

The highlight was getting over Pawnee Pass. Overcoming the mental and physical stress was a great accomplishment. I have hiked steep places. Bear Peak is the most challenging hike in Boulder because it is steep, climbing 3,000 feet in four miles to 8,200 feet. Mount Lemon on the AZT was the most demanding hike because it was very steep, requiring some scrambling to 8,800 feet. However, Pawnee Pass beats them all. It is more vertical, requires some scrambling, and is much higher, topping out at 12,550 feet, and includes some danger.

People I met on this hike did not care that I caught them or compared equipment with me. When I hike alone, I can do 18-25 miles in most situations, including good climbs. I am a lightweight hiker, and I do more miles than the average person. I made this hike my hike.

Recording My Trip

I took more photos and videos and can do even more, especially about my campsite and eating. Picking a campsite, setting up camp, eating, and breaking down camp are mundane activities, and I do them every day when in the backcountry. Sometimes the seemingly dull activities are engaging.

Logistics Stress

I love not stressing about logistics. I want to learn how to let all logistics stress go. End-to-end versus loop introduces logistics stress, as do multi-week/month trips. How can I resupply in towns without good food and hygiene choices? How can I reduce or eliminate the stress of not knowing how to get to or from a trailhead?

The AZT taught me that I could resupply in a large town, and I got to trailheads with the help of friends and blogs. I still stressed about the pickup from the state-line campground at the end, even though I had help from Kharen. Kharen helped reduce my burden by taking some of the responsibility of finding rides and ultimately had success. Therefore, I did not experience the accomplishment. On my f-up, I successfully hitched and found public transport. Regardless, I need to be confident that I will find a ride and not worry when doing all my adventures. Let the stress go; stressing does not accomplish anything.

Mind Worms

Mind worms are inevitable for me. The monotony of hiking causes my mind to wander, and sometimes I think about negative things like why I am doing this and need to do something meaningful rather than be backpacking. I usually listen to music, podcasts, or audiobooks to focus on something else. When the weather closes in, the views are amazing, the wildlife reveals itself, or navigation is tricky, I engage my mind, so I never get negative thoughts. Mind worms were the source of my f-up.

On both days, there were times when a mind worm entered my thoughts, asking myself why I was doing this and thinking I should sell all my gear. I found that the key to minimizing mind worms is to list why I am doing an and what I will feel not making the trip. I also control the “meaningful” activities by getting them done beforehand. Since this was a short trip, I could ignore “meaningful” tasks for a few days.