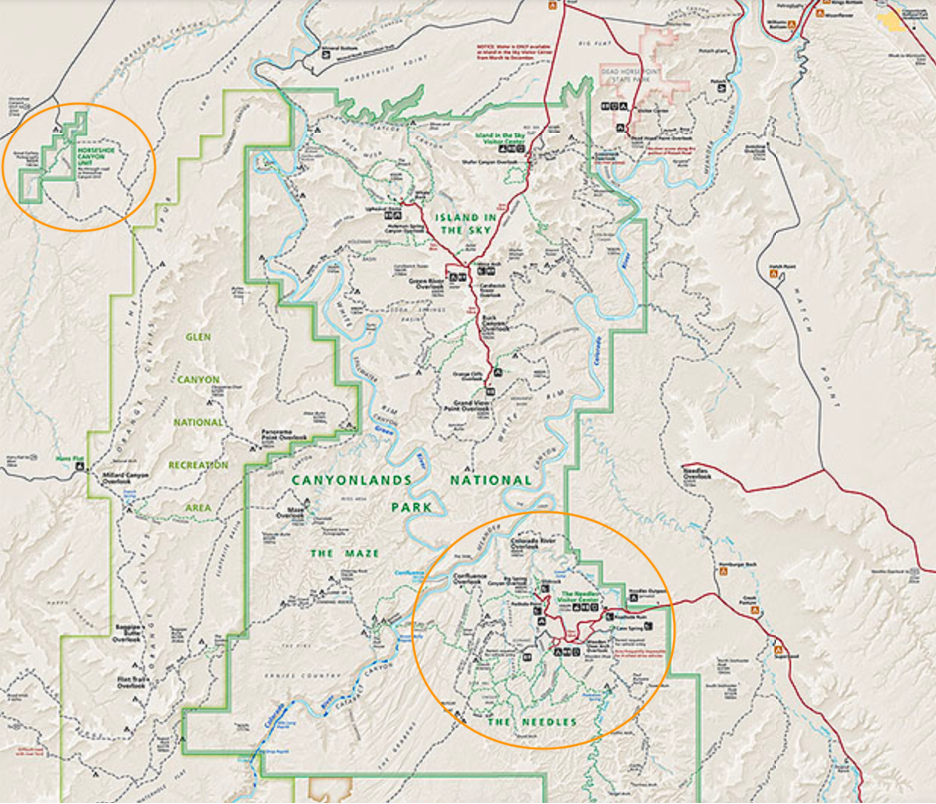

I took my first trip to Canyonlands and fell in love with the rock art and wonderous rock formations of the Needles District. In both cases, I camped on BLM land and did day hikes into the park. The Horseshoe Canyon and Druid Arch are in separate parts of the park and require driving.

Horseshoe Canyon is remote, and the attraction is the “Great Galler” of pictographs. In Horseshoe canyon, there are multiple pictograph sites. I was attracted to Horseshoe canyon because of my trip to southeastern Colorado to see Native American rock art. Unfortunately, vandals defaced the rock art, so I wanted to see pictographs in better shape. The ones in Horseshoe Canyon are of unique human forms and are much older. According to archeologists, the art is 4,000 years old.

Furthermore, there are dinosaur footprints, a bonus” “Horseshoe Canyon is remote, and the attraction is the”Great Gallery” of pictographs. In Horseshoe canyon, there are multiple pictograph sites. I was attracted to Horseshoe canyon because of my trip to southeastern Colorado to see Native American rock art. Unfortunately, vandals defaced the rock art, so I wanted to see pictographs in better shape. The ones in Horseshoe Canyon are of unique human forms and are much older. According to archeologists, the art is 4,000 years old.

My attraction to Druid Arch is because the rock formation is very dramatic. The arch is enormous and appears to be two rock columns with another rock spanning the columns. I could not get backcountry permits for Canyonlands National Park because of the spring break crowd. However, an old, grizzled backpacker told me the secret is to go to the backcountry office when you arrive and see if anything is available since people cancel or do not show.

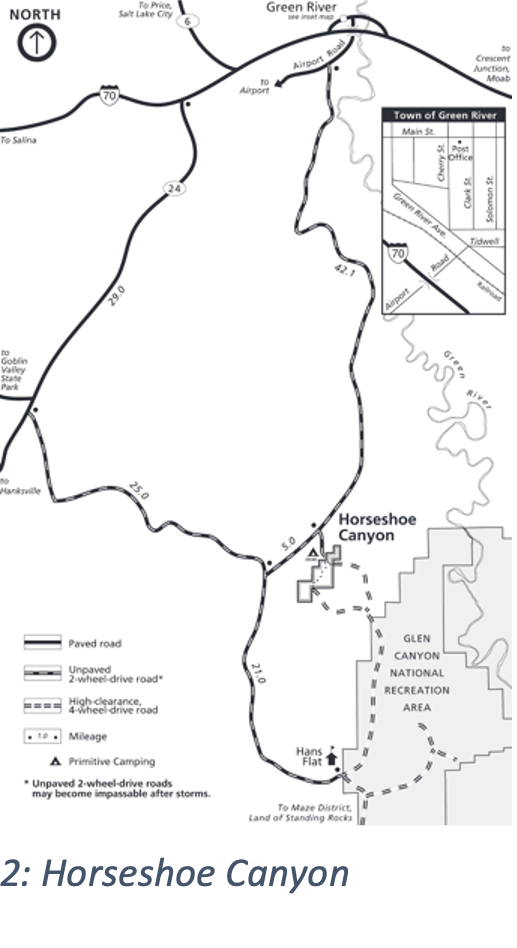

Horseshoe Canyon is remote, 46 miles from Green River, Utah, on dirt roads. I learned an important lesson when leaving the canyon without a map or cell service; finding my way-out using landmarks failed. I knew where I needed to go, but which roads to take was a trial-and-error process. Dead ends were everywhere, and the worst event would be to get stuck in the sand. I made my way to the road without mishap, but it took longer than anticipated. I will always carry a map or plot my routes for offline use.

I left Boulder at 08:00 and got to Horseshoe Canyon at 15:00. There was a handful of cars camping, and a few departed before sundown. I quickly found a campsite. The V-stakes I brought did not work well in the hard soil, so I weighted them down with rocks.

I met a woman from Orcas Island, Washington, who had just finished hiking the canyon. Previously, she had camped at the Islands in the Sky District of Canyonlands, where she had spent two days. She raved about the beauty of the rock formations but was disappointed with the crowds. Unfortunately, strong winds had buckled her tent poles when she was hiking on the last day in Islands in the Sky, so she was sleeping in the back of her Subaru wagon. She loved Horseshoe Canyon, saying it differed from Islands in the Sky since it was more isolated, compact, and with fewer crowds.

One car arrived after dark when all the campers at the trailhead had retired. I awoke as I imagined most people did with the car’s headlights, and they crashed into a primitive stone campfire pit. When I left for my day hike, they were still asleep, but I ran into them, two twenty-something boys, on my walk out from the canyon the next day. They were vaping and hiking to the Great Gallery, stoners who had not learned that the world does not revolve around them. Getting disturbed at night and in the morning is expected when camping at group sites. I ignore it since someday I might have to arrive late and not even be stoned. Karma!

The attraction to Horseshoe Canyon is the well-preserved pictographs and petroglyphs from 4,000 years ago. The surrounding land is non-descript and arid, with some cows. Going west from Horseshoe Canyon are the Islands in the Sky District of Canyonlands and Arches National Parks, which are far from non-descript. Both parks are trendy and close to Moab, attracting mountain bikers and off-road enthusiasts.

I got up soon after the sun rose, planning on starting the 7.5-mile roundtrip hike into the canyon to go down to the Great Gallery. On the way, I was planning on seeing the smaller rock painting sites and some dinosaur tracks. I enjoyed coffee and breakfast as I packed up. I believe in packing daily to avoid accidents when leaving my gear setup. I’ve heard too many stories of nature-damaging gear or good Samaritans believing the campsite is abandoned and giving the equipment to a ranger. As a result, the people who “abandoned” the gear return to find all their gear and food missing and spend time tracking it down. Being a backpacker, I travel light and can pack quickly.

I love hiking in the morning. It is quiet, and the light is very different. I also like that the animals are starting their day and grazing or foraging. I came across a herd of deer in the canyon. When I spoke to the ranger who was hiking to the Great Gallery as I was returning, I told her of the deer encounter; there was a herd of at least seven deer. She said she had seen scat and footprints but had never seen the deer. I was surprised and realized that maybe the deer and I had something in common: we enjoyed the quiet serenity of the morning. In truth, I was also excited to see the rock paintings and have time to admire and contemplate them in the peaceful morning.

The hike into the canyon was easy, with about 700 feet of elevation change for about a mile. Since this was an out-and-back hike, I usually take my time on the way-out admiring nature, looking around, and taking pictures. My return trip is usually much faster.

The patterns and colors in the rock made by erosion and the forces of nature catch my eye, and photos cannot do them justice. I get wonderfully distracted and hike at about two mph with all the stops and looking around. I have not mastered looking up and all around while walking, so I lollygag. The lollygagging is worth it, which is why I enjoy the mornings.

Navigation is easy, and there is no worry about getting lost since the canyon is relatively narrow with limited access points. There is one branch trail to the east about midway down the canyon. That branch trail provides access from a trailhead accessible to 4-WD vehicles. I did not need my GPS and “discovered” the rock paintings at Horseshoe Shelter. I initially caught a glimpse of them partially hidden by a rise and Juniper trees. Trip reports gave me the locations of all the picture sites, but I did not record the actual locations. Instead, I enjoyed “discovering” them.

The canyon has four rock painting locations; the largest is the Great Gallery. Experts have dated the oldest to be 4,000 years old. Several years ago, two hikers found a leather bag revealed by a natural flood in the canyon. They reported the find to the NPS ranger. The NPS recovered and preserved the bag, which contained seeds and several tools for forming leather from animal hides. They dated the sack at 2,000 years old.

The canyon has a dry riverbed, which last saw significant water (3 feet) four years ago. Plant life consists of Juniper trees, sage, and other hardy plants that can survive the dry, harsh climate. There were a couple of Indian Paintbrush plants with bright red flowers. Plants were coming alive with the spring weather. Doing this in summer would be very uncomfortable when temperatures get over 100 degrees.

The rock formations were out of this world. Erosion over the eons exposed swirls in the sandstones. The heat would cause cracks in the hard rock which would break from the water that would seep into the cracks and then freeze in the winter. I came across a vast amphitheater, which was nearly fifty feet high. It was an echo chamber. I found it very interesting that the only trace of the rock that filled in the theater is on the sides and that the arena is almost clear of debris. I imagine the harsh summer heat and freezing winters fractured the boulders and stones over time. Then when the canyon flooded, the boulders, gravel, and sand were distributed and moved out of the arena. Regardless, the sound would echo in the theater.

The primary reason to venture to Horseshoe Canyon is the rock paintings. No one knows the meanings of the paintings. I imagined that the paintings depicted some ceremonial events, perhaps the death and morning of great leaders or visits by other tribes. The interesting point is that the people who created the paintings put them high enough on the canyon walls to protect the paintings when the canyon floods and from vandals.

The Great Gallery site has the most and most prominent figures. The enormous figures at the Great Gallery are more than 4 feet high. Most figures lack arms and legs, and some appear with skeletal faces. There are some animals and a few human-looking figures.

When I arrived at the wall, no one was around, and I could go up to the wall and look closer and contemplate the different figures. I was attracted to the gaunt faces of some humanlike forms, wondering what the artist was trying to depict. Did the paintings represent death? Why did most of the figures have broad shoulders without arms or legs? Were these supernatural or something simple like figures with blankets? What did the geometric designs on the figures represent? Why were these pictures made? The hair of some figures was fascinating, with spikes or ornate. What did the skeleton head mean? There were some animals; perhaps some were deer with antlers. Others looked smaller, maybe dogs?

I sat and looked at the wall from a distance and then as close as possible. I did not expect to figure it all out. I thought about the archeologists and experts in native American art that studied these art pieces. The galleries are lovely and worth the effort. I want to find more good examples of Native American art (Salt Creek in the Needles district of Canyonlands is one.) I spent about one hour at the four pictograph sites. They are captivating and unique.

When I ran into the ranger on my return trip, she said we didn’t know what the paintings meant or represented. Only recently, we could date the images between 2000 and 4000 years. DNA and interpretation of some of the drawings helped date the pictures using the recent discovery of the leather bag. She said that these paintings give rise to more questions than answers.

The ranger lives in a small trailer about 100 yards up a small hill from the trailhead. The NPS has rangers to help protect and answer questions from visitors to Horseshoe Canyon. They are in rotating shifts of one to two weeks.

I got back to the trailhead around noon. The day warmed up and without clouds. Off I went. Unfortunately, I did not have a map of the dirt roads leading to Horseshoe Canyon, but I thought I could remember the route to Green River. Guess what? I made a wrong turn and got lost. I spend two hours trying to find my way. I ran into dead ends and was on some very sketchy roads. I did have the foresight to have plenty of gas, and I thought that if I did get stuck, I had a satellite communicator, plenty of water for a week, and food, although I did not want to have to pay the cost of getting towed out.

After about an hour of searching and realizing that I could not even find my way back to Horseshoe Canyon, I thought I would head south, and I hoped I would eventually run into the road that led to Route 24. I also stopped taking random unmaintained roads, which led to dead ends or progressively worsened the further I drove, and I would likely end up stuck. As long as the route trended south and was reasonably maintained, I took it. Roads that got worse as I went, I turned around and found another way. Finally, I saw a more significant road headed east-west in the distance. I hoped that this was my exit from this maze. I was lucky that it was. I saw a camper van heading west and followed it, eventually getting to Route 24. Going north, I got to Green River and then I-70.

I could locate where I was using GAIA GPS, but I had not downloaded offroad roads, so I could not find a route.

I headed to the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park from Moab. I arrived around 17:00 at the Super Bowl BLM campground and found a spot. Many schools were on spring break, so the campground was almost filled. When I was setting up camp, a storm came through, which blew up dust and had a small amount of rain. I set up fine and weighted down the stakes with rocks. The wind kept up until 9 PM and then died down. The fine powdered dust got into everything. Between the wind and dust, I simplified dinner to a few Larabars and RXBars since the wind was formidable, making cooking something almost impossible and the food I brought was not cold soaking material. The temperature was delightful, getting down to 46 degrees. I got up at dawn, used the vault toilet, had a great breakfast of cheesy potatoes and coffee, and set off for the 5-mile drive to Canyonlands National Park.

After a few miles, the slick rock trail descended and returned to a dirt trail. Off the path, there are soil crusts, which are lumpy, dark, and fragile. I never saw biological soil crusts before, but it is standard worldwide in deserts, even Antarctica. The soil crust is vital since it is resistant to erosion and absorbs and stores water. The trail passed through lots of this, and the route was easy to follow. I understand why dogs are prohibited since they would damage the soil crust as they explore.

I passed through a couple of slot canyons and descended to a sandy, dry riverbed, making hiking more difficult. Having gaiters would help prevent getting sand into my shoes and socks.

I ran into a park ranger who was hiking to Druid Arch too. It was his first time to the arch, and he was unsure of the path. I used GAIA GPS and was able to confirm our direction. He was friendly and knowledgeable about the park, even though he had trouble navigating. Canyonlands is a good size park at over 337,000 acres. In comparison, Yellowstone National Park is 2.2 million acres, and Yellowstone is not even the largest national park. The Canyonlands National Park is big, so I understand that rangers do not know everything.

I left the ranger behind when he started answering a couple’s questions and ran into another couple from Oregon and a man from Denver, Bob, an architect. The trail left the dry canyon and became more rugged, requiring some scrambling. It was not difficult and required patience and ensuring each step was secure. The last stretch to the arch was steep, but the view of the arch was breathtaking. The arch is over 200 feet high.

I rested and had some food. Bob and I talked about the park. At the campground the day before, I relayed that a gentleman told me that the NPS consulted with Native Americans about laying out the trail system. We both agreed that the trails were excellent. Bob said that he had completed a few footpaths in the park and that no two are alike. I commented that I wondered how Native Americans felt about us taking over their lands, but at least the NPS consulted them with respect and tried to preserve and respect their lands.

I digress, but this is a remarkable story Bob told me. Bob said that his firm designed the NOAA building (David E. Skaggs Research Center, completed in 1998) on existing federal lands next to the NIST building in Boulder on Broadway. He said that in the public hearings, there was opposition to the NOAA building, and that resistance was not because the design was terrible but because people still wanted to hike through the area. The NOAA argument was that the building would not prevent hiking in the space, nor did it damage the land, which was bush. NOAA countered all opposition in the hearing until a man said the ground was sacred Native American land.

That put the project on hold. The Department of Commerce contacted all the Native American Tribes known to have spent time on the land (Arapahos, Utes, Comanches, and Sioux) and flew them to Boulder to examine the ground. Twelve tribal representatives arrived two weeks later and said the land was not sacred to any of them. Bob was relieved and admitted that he thought NOAA would cancel the project.

Getting back to Canyonlands, I was a little nervous about going down. For me, ascending is easier to do than descending. However, the way I look at this is (a) other people have been successful, so I can too, (b) I will gain experience, (c) I can’t stay here forever. The descent was easy. One area I needed to scramble on the ascent was simple when descending, as long as I ensured my footing was solid.

The rest of the hike back went well. The temperature was in the mid-seventies causing me to sweat a little. I had not showered in three days but used Wilderness Wipes to remain somewhat sanitary. When I stopped for ten minutes in the shade on the hike back, I could smell myself. Wow! I was wearing an antimicrobial shirt and thought it had failed. I did not realize that when the top dries, it does not smell, but when it is wet with sweat, it may stink.

About a mile from the trailhead, I seemingly ran out of water. I’ve never run out of water in recent memory. When I got back, I had water waiting and looked at the hydration bladder. It still had almost a half-liter, so the rest of the pack contents had pushed the water away from the drinking tube. Another lesson learned. I do day hikes with a small pack and hydration bladder and do overnights with SmartWater bottles. The reason is that with SmartWater bottles, I can tell how much water I have, and with a hydration bladder inside my pack, it is hidden, and I cannot see how much water I have unless I stop and examine the bladder.

I will start hiking with SmartWater bottles always. Besides knowing how much water I have, the bladder mouthpiece freezes below 25 degrees even when blowing back and clearing the tube because the tube’s mouthpiece still has water and freezes. Besides, the bladder weighs almost a half-pound more than SmartWater bottles.

I headed back to the BLM Superbowl Campground. I saw three tents that had blown around because the people kept their tents pitched, and the wind became strong in the afternoon. Others in the campground had secured the tents.

I evaluated the weather. The wind was going to gust to 45 mph that evening and night, and Boulder would get snow the next day. It was about 4 PM, and the drive back would get me home at around 11:30 PM. Did I want to endure a crappy night at the campground and then drive sleepy?

I drove that evening and got a couple of Cokes to help me stay awake. It was the correct call because Boulder got about a foot of snow, which would have made driving home longer and more arduous.

In summary, I got a great taste of Canyonlands and want to return in the fall and try hard for a backcountry permit. I want to camp in Chesler Park, which is supposed to be unique. If I cannot get Chesler Park, then Elephant Canyon, Lost Canyon, or The Grabens are suggested. May 10th is the opening day for getting a backcountry permit after September 10th.